Introduction

This is a page devoted to my favourite books, most of which I read

regularly. The bookmarks below, which are sorted in order of ascending

publication date, will lead you to my thoughts and opinions on these

books, and why I like them.

As anyone who has visited us will be aware, Kerry and I aspire to be

bibliophiles, and have amassed a large and varied assortment of books.

Many of these books have been purchased from Clouston & Hall Booksellers, otherwise known as Academic Remainders. If you are into books, get onto their catalog list.

David.

Contents

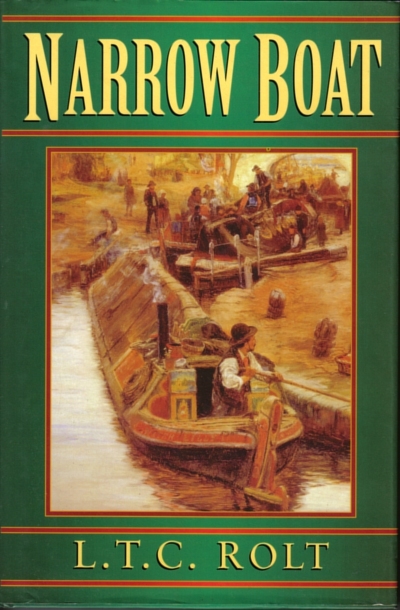

"NARROW BOAT" by L T C Rolt 1944

"A Wop Bopa Loo Bop A Lop Bam Boom - Pop From the Beginning" by Nik Cohn 1969

"The Book of HEROIC FAILURES" by Stephen Pile 1979

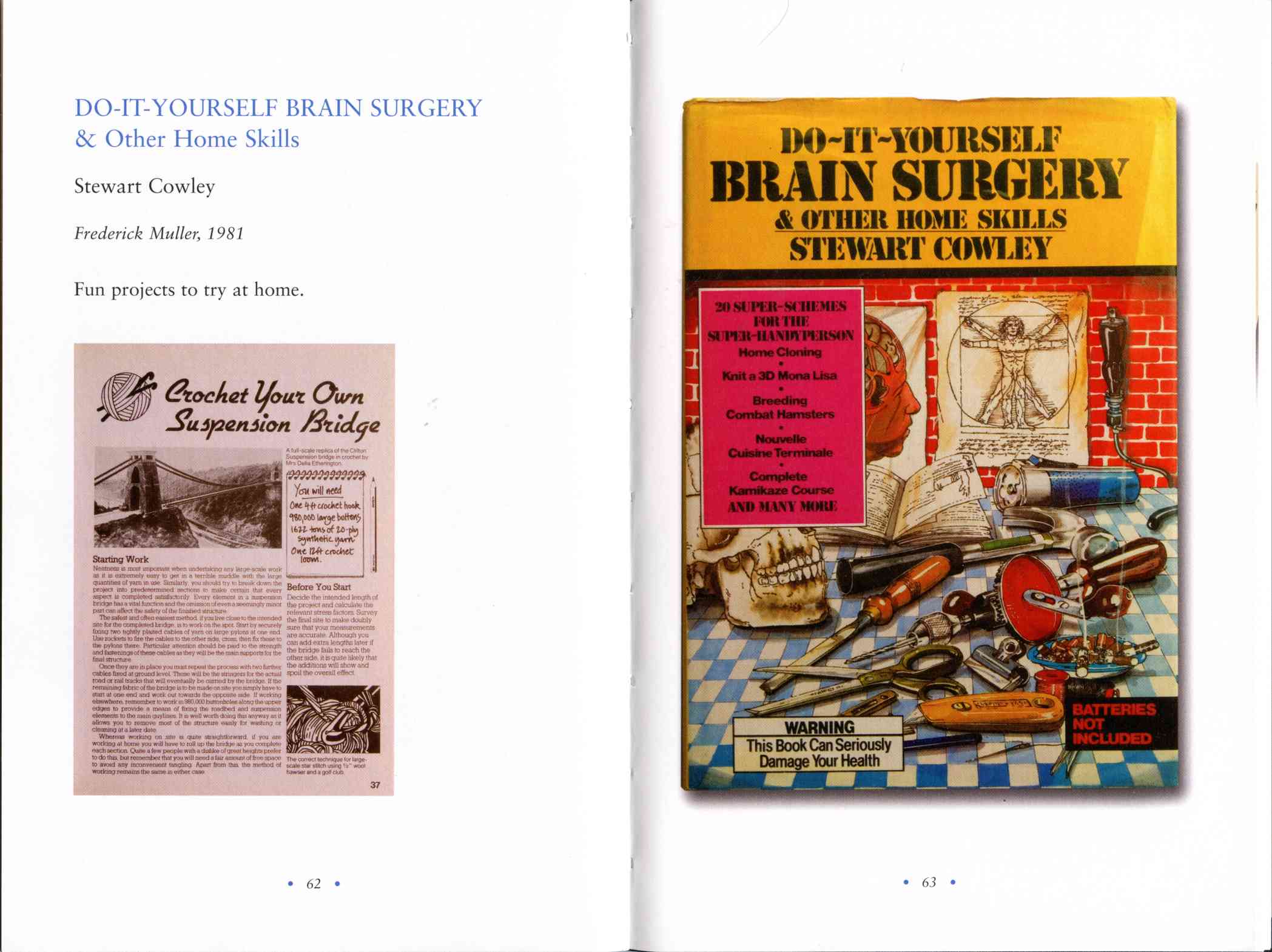

"Do-it-yourself BRAIN SURGERY & other home skills" by Stewart Cowley 1981

"Cheats at Work - An Anthopology of Workplace Crime" by Gerald Mars 1982

"The Penguin Dictionary of CURIOUS and INTERESTING NUMBERS" by David Wells 1986

"TREK" by Paul Stewart 1991

"The Secret Life of the MORRIS MINOR" by Karen Pender 1995

"The Mummies of Urumchi" by Elizabeth Wayland Barber 1999

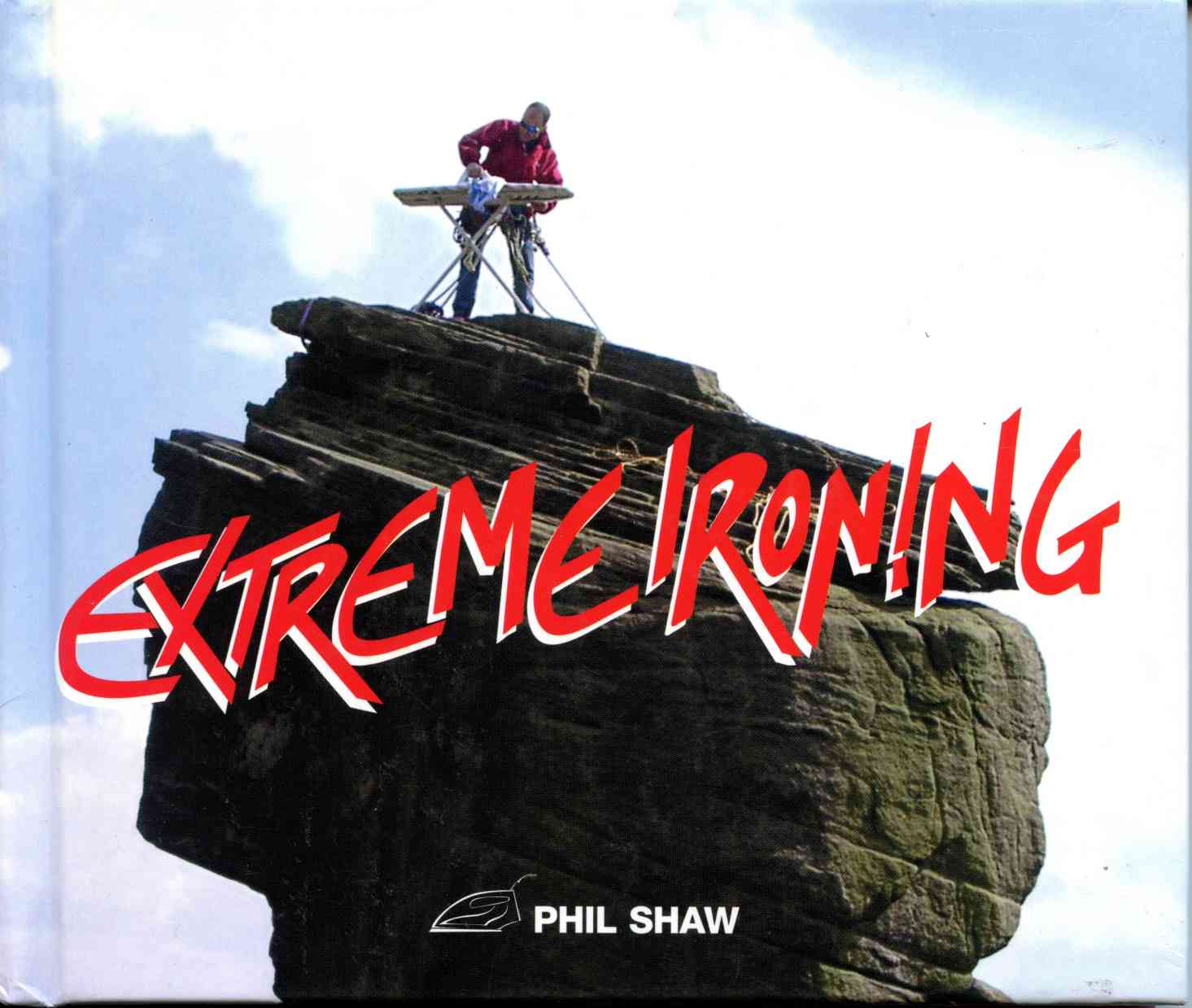

"Extreme Ironing" by Phil Shaw 2003

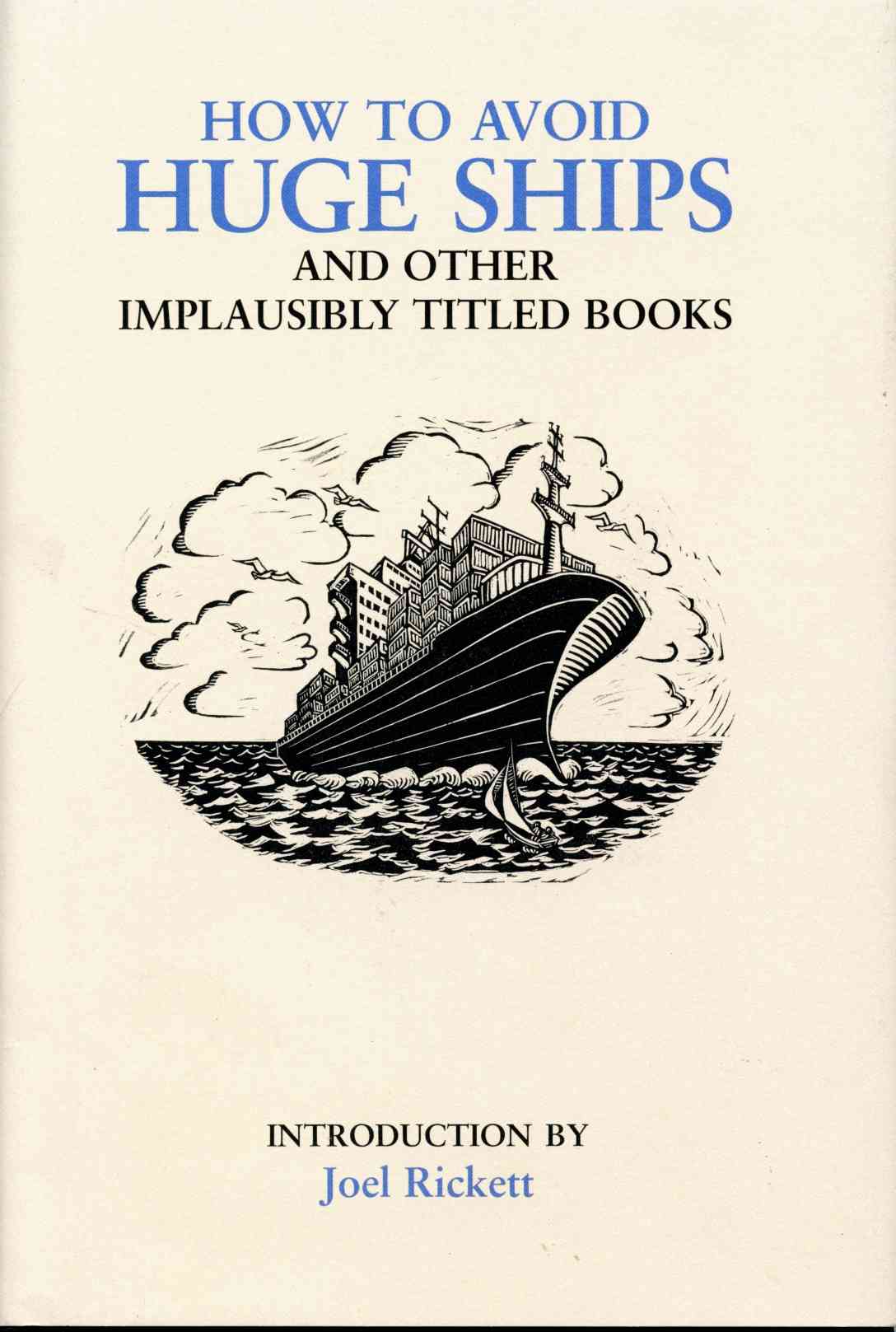

"How to Avoid Huge Ships" by Joel Rickett 2008

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

A Wop Bopa Loo Bop A Lop Bam Boom - Pop From the Beginning"

by Nik Cohn, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd, 1969 ISBN unknown

I bought this book when I was at University (1969 - 1972) and starting

to get interested in Rock and Roll. My paperback copy still has the

plastic cover I put on it (just like all my text books!), but is

starting to fall apart.

Hank Williams gets several mentions, and the comments on the Rolling

Stones (in the caption to the photograph between pages 128 and 129 are

spot on.

I now have many other books on Pop and Rock and Roll, but this is still one of the best.

David Edwards August 2007

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

Cheats at Work - An Anthopology of Workplace Crime"

by Gerald Mars, George Allen and Unwin, 1982, paperback ISBN 0 04 301 166 7

First of all, let me state clearly that I consider myself to be honest. That said, this book is a delight to read.

As a study in human nature, it explains a great deal about life in the

workplace. Gerald's classification of people into hawks, donkeys,

wolves or vultures is very different from the standard Myers-Briggs

classification, and probably more accurate.

Ask your local library for a copy, or search for it on the WWW. It is well worth the read.

David Edwards August 2007

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

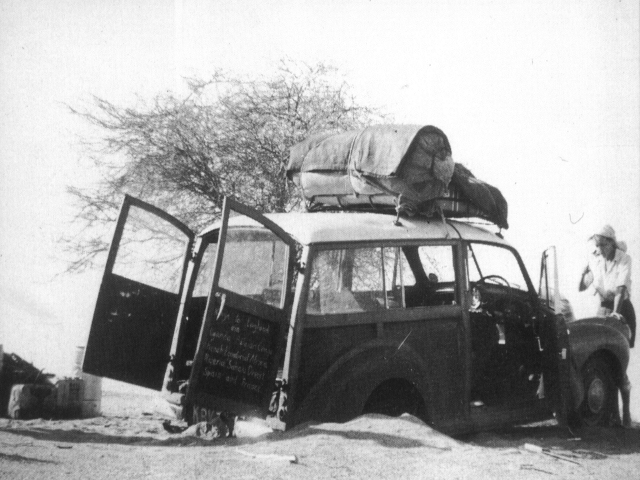

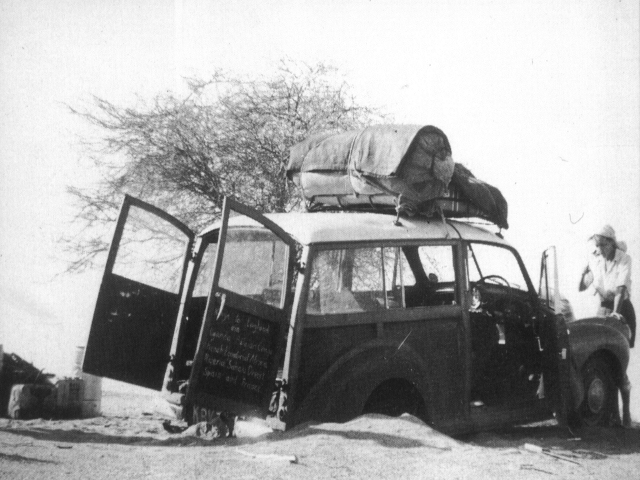

TREK

by Paul Stewart, Jonathon Cape, 1991

I wrote this review for the Morris Minor Car Club of Tasmania in 1999.

The Ryde Library was recently able to find and loan me a copy, as my

original copy is still in Tasmania.

TREK

“Car

crossing Africa, Sahara, Spain, France

for England, leaving Kenya last

fortnight April, has room for six passengers. Full particulars from Voucher

X905.”

This advertisement appeared in the personal

columns of the East African Standard on Saturday, 15 January 1955. It was

placed by Alan Cooper, a forty-seven year old Kenyan farmer who had decided to

travel back to England

to visit his eighty-four year old mother. However, Alan’s farm was not a great

commercial success, and travel by normal methods was beyond Alan’s means. The

rationale behind the advertisement was that by taking paying passengers with

him, Alan could effectively travel to England at no cost to himself.

The proposed trip had some logic behind it.

In 1933, Alan and a single companion had travelled to England just

this way, in an 8 h.p. two seater side valve Morris Minor. They travelled 8,000

miles from Nairobi to London,

via Uganda, the Sudan, the Congo,

the Cameroons, Nigeria, the

Sahara, Algeria, Morocco, Spain

and France.

The 800 mile trip across the desert, between Gao and Reggan, took four days.

Alan planned to use two cars on the 1955

trip, a Morris Oxford estate car and a half ton Morris commercial truck. Four

people would travel in the Oxford,

and three in the truck. But Alan did not get sufficient suitable takers, and

the trip was scaled down. In the end, there were only three passengers, and the

two vehicles had been reduced to a single Series II O.H.V. Morris Minor

Traveller, registration number KBY-779.

The three passengers were a mixed bag. Peter

Barnes was a seventeen year old youth from Kenya,

packed off by his mother to be “toughened up”, and to visit his relatives in England.

Barbara Duthy was a forty year old unmarried zoologist (she specialised in

worms) who worked for the Kenya Government. Freda Taylor was a primary school

teacher from England, who

jumped at the chance to extend her leave and travel back to England by a

more adventurous route. Freda was unmarried, and claimed to be thirty-eight,

but in fact she was fifty-five.

Even before the trip started, things were

going wrong. Alan picked up Peter and Barbara from Mubosoni in the Traveller,

and on the way back to his farm in torrential rain and thick fog, as recorded

in Peter’s diary, “He drove furiously along the wet, slippery road, and

rounding a bend at 40 miles per hour, we went sideways into the bank”. As we

all know Morris Minors, even those with outside wooden framing, are strongly

built, and only Alan’s pride was dented.

The four adventurers started their trip on

Friday 5 April 1955. Alan and Peter shared the driving. Their planned route

would retrace Alan’s journey in 1933, except that they were planning to take a

different, sandier route through the Sahara

Desert. The Traveller was

somewhat overloaded, with four adults, all their gear and food. Alan saved

space and weight by leaving out most of the spares, tools and traction aids

recommended by knowledgeable travellers. The rear was packed to the roof

lining, with the overflow carried on a roof rack.

There were many minor mishaps on the way,

such as spilling paraffin into the large metal trunk containing all the food

and losing the keys to the back doors. They camped every night, which meant

unpacking the car on arrival, and re-packing it in the morning. Alan insisted

on travelling at least 200 miles every day, which meant they had little time

for sightseeing. Tempers became frayed.

The first major calamity occurred not long

after they crossed the border into the Cameroons.

On what appeared to be a good road, and in order to make up time, they were

cruising at about 40 mph when a “large rock bounced up”, and made contact with

metal under the car. Alan refused to stop, on the basis that the damage was

only to the exhaust. It wasn’t: several miles further on the oil pressure

warning light came on.

This time Alan stopped, and they all got out

and surveyed the thin broken line of oil which led back to the rock. Alan had

something to plug the hole in the sump, but he had no spare oil, so they had to

wait until an obliging lorry pulled up and provided some. With the engine

knocking ominously, they continued slowly on to Maidaguru in Nigeria, where

repairs to an English car would be more feasible.

They reached Maidaguru at noon the next day,

with the engine knocking continuously. The local garage soon delivered the

expected diagnosis: a blown big bearing on the number three cylinder. They

waited several days for spares to be flown in on the weekly plane, but when the

plane arrived, the spares didn’t. So the local mechanic re-flashed the worn

bearings with white metal, completing the job at about 3pm on Sunday 1 May.

They left immediately, as the road across the

Sahara was scheduled to be closed on 15 May.

The mechanic had recommended that the motor should be run in for 50 miles, so

Alan kept the speed down for that long, and then commenced to accelerate. It

didn’t take long for the engine to start knocking again.

They managed to nurse the car to Kano, where new bearings

were fitted. The damaged crankshaft was not repaired, as access to the big ends

was obtained by simply removing the sump. At Kano, Alan refused an offer to

travel in convoy with a Landrover, and they reached the border with French Equatorial

Africa 21 days and 3,239 miles after starting, having averaged over 150 miles

each day.

350 miles north of Kano,

and well on the way to the start of the Sahara Desert

at Agadès, the engine started knocking again. Alan had purchased a spare set of

bearings in Kano,

so they stopped over a convenient rut, and he drained the oil from the sump.

Only then did he discover that none of his spanners fitted the sump bolts!

Refilling the sump, they continued slowly on to Agadès, where it was

planned to get the replacement bearings fitted.

At Agadès a French military

mechanic installed the replacement bearings. Peter had to trudge off through

the heat to purchase oil from the local garage, as oil was not available from

the military. Alan was still not carrying any oil!

The French Military (the Foreign Legion) had

strict requirements travellers needed to fulfil before attempting the desert

crossing. As well as a refundable £50 pound deposit for each

traveler (to cover rescue costs), each car had to carry a 50% reserve of petrol

and oil, a water reserve of twice the radiator capacity, 5 gallons of water per

person plus their normal daily ration of a gallon per day, and railing or wire

netting to allow the vehicle to be extricated from sand. Even more importantly,

vehicles should be “in perfect mechanical order”. It was highly likely that the

overloaded Traveller would not be approved for the desert crossing because of

limited ground clearance.

Knowing this, and without

telling his passengers, and without notifying the authorities, as soon as the

car was repaired, Alan told them he had obtained permission, and they left

Agadès late on Sunday 8 May. Unbeknownst to the passengers, Alan had not

registered with the authorities, and no one knew they were leaving. They camped

that night after traveling only 50 miles.

The next day the road

petered out, and they were forced to navigate using the bidons (44 gallon fuel

drums cut in half, filled with sand and gravel and painted black) spaced at 1

kilometer intervals. 30 miles from the In Abbangarit oasis, they bogged the

car. Luckily they were able to push it out, and then continue on to the oasis,

where they refilled all their water containers, as well as couple of jam jars

“just in case”!

At noon they stopped next to

two lone trees about half a mile from the track, and created some shade using a

tarpaulin stretched between the trees and the car. While it was a good idea to

stop and rest in the heat of the day, Alan should have realised that drifting

sand accumulated near any obstacle. When they decided to move on at about

2:30pm, the car immediately sank up to the rear axle into the sand.

Three hours later, they had

emptied the car, and managed to move it 20 yards back to firm ground. They

still had to carry all the equipment back and re-stow it, and they were all

exhausted once this had been accomplished. They bogged again five more times

that day, principally because Alan insisted on driving close to the bidons

where the drifting sand accumulated. The last time they were too exhausted to

continue, so they set up camp instead. Only 4 gallons of potable water

remained.

Stuck

in the sand for 5 hours 15 miles north of In Abbangarit

After they unloaded the car

the next morning, the others pushed and heaved while Freda (the lightest)

drove. Once the car was freed, the others watched while she continued to firm

ground. It was several hundred yards away. It took each of the four three trips

to carry all the gear across to the car. They finished at 5:45am. At noon that

day they were stuck for the fourth time that day, and too exhausted to

continue. There were only ten pints of water remaining, and it was 60 miles to

the next oasis at In Guezzam.

Peter suggested he should

walk the 6o miles for help, but in the end Alan over-rode him and set off just

on dusk. As the remaining male, Peter decided he would free the car. Five hours

later, after much jacking to allow the mattresses to be fitted under the

wheels, he freed the car. After a brief sleep, they woke at 3:30am and

commenced loading the car, so as to be ready to leave at dawn, hoping to catch

up with Alan.

After covering only 17 miles in three hours,

they reached an area of rocky ground where they could increase speed to 35 mph.

The cooling breezes generated were appreciated by them all. Almost immediately,

however, they ploughed into soft sand again, and once more the Morris dug in to

the axles. All they could do was sit in the car and wait for the cool of night.

By half past ten that night, Peter had

managed to extricate the car. Only then did they decide to jettison some of

their baggage. Leaving at 4:30am, they bogged four times in the first five

miles. They had two pints of water and were still 30 miles from the oasis.

By this time, they were used to the desert

mirages, so it took some time for them to realise that the two approaching

vehicles were real. The three ton Citroën lorry and accompanying

Volkswagen had found Alan collapsed on the sand about 25 miles from In

Guezzam. He had been minutes from death.

Alan, partly delirious from

heat exhaustion, wanted to continue, but was over-ruled by his passengers. With

the Morris easily freed by the lorry passengers, they turned south and headed

back to In Abbangarit, traveling in a convoy of three. Peter commenced driving

the Morris, with Barbara and Freda as passengers, but after they bogged

innumerable times in the first half hour, he was replaced by fourteen year old

Ali, who proved adept at avoiding soft sand. The next stop was to retrieve

their abandoned belongings.

Alan’s condition was deteriorating, and the

lorry driver could not concentrate on his patient and on Alan, so it was

decided to shuffle passengers. Alan was placed in the front seat of the Morris,

with Freda in the rear and Peter driving. Barbara took Alan’s place in the

lorry. The Traveller lead the convoy, with strict instructions to all that they

must stop if the Volkswagen stopped. The Citroën lorry brought

up the rear.

With all the luggage in the rear of the

Traveller, Peter could not see behind, so it was up to Freda to keep the

following cars in sight. Alan was slipping in and out of consciousness, and

Freda, herself suffering from dehydration, could not minister to Alan and look

behind at the same time.

Only about 1 hour from safety at In

Abbangarit, Peter and Freda realised that the other vehicles were not behind

them. As he had been instructed, Peter immediately stopped, halfway up a

shallow rise. The jolt woke Alan, and he convinced both Peter and Freda that

they should continue. With no tracks to follow, Peter continued up the shallow

rise and down the other side. The Morris immediately sank in soft sand up to

the axles. They had no water, so Peter drained the radiator.

They flashed the car lights

for hours that night, but no rescuers appeared. The next day was Friday 13 May.

At 9am Peter climbed to the top of the rise, and saw the Volkswagen searching

for them. Unfortunately, the Volkswagen did not see him. At 8:30pm that night,

Alan died.

In his anger and grief, Peter decided to free

the car. With only the strength to crawl, it took him eight hours. Freda could

not countenance leaving Alan’s body, so they laboriously dragged it into the

rear of the Traveller. They drove on, with the engine knocking violently and

overheating because of the lack of radiator water. They had to stop every 3

miles to let it cool. After 12 miles, it refused to start, and Peter was too

weak to turn the crank.

As dawn broke, they realised the end was in

sight. Alan’s body began to decompose, so Peter hauled it out and round to the

shade at the side of the car. At noon Freda was delirious and ripped off all

her clothes in a futile attempt to cool down. By 1:30 pm she was dead. Peter

got out of the car and took one last photo with his Box Brownie. It is blurred

because he could not hold the camera still. At about 2 pm he lay down in the

shade next to the Morris.

At 5:30pm on 15 May the search party, which

had only set out after Barbara and the remains of the convoy had reached Agadès

(240 miles away) and notified the authorities, found the Morris. Peter was only

just alive.

While Peter and Barbara recovered from their

ordeal, the car was towed to Agadès and repaired. At 4 pm on 8 June, Peter and

Barbara drove it back to Kano in Nigeria. The

monsoon rains had arrived, and the roads were a boggy quagmire. From there they

flew to England.

This article is based on the

book “TREK”, written by Paul Stewart, and published by Jonathon Cape

in 1991. I purchased my copy at a remainder book sale a few years ago. The full

story makes a gripping reading. As a Morris enthusiast, it seems clear to me

that the main cause of the tragedy was Alan Cooper’s lack of preparation and

decision to attempt the desert crossing without proper equipment and without

notifying the authorities. The Traveller coped surprisingly well with the

conditions and the abuse it was subjected to.

Kerry has determined that

the State Library of Tasmania has at least three copies of this book.

David Edwards August 2007

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

The Secret Life of the MORRIS MINOR

by Karen Pender, Veloce Publishing 1995, hardback ISBN 1 874105 553

I bought this from the Technical Book Co in Melbourne. It is a

brilliant book, as Karen has clearly had similar experiences to me.

My

introduction to hydraulic brakes was in 1969, when the brakes on my

1952 2 door Morris Minor sedan failed as I came down the hill into

Bellerieve from South Arm. It was only after dismantling all the wheel

cylinders in all the wheels did I discover that the lack of brakes was

caused by a lack of brake fluid, and that to get the master cylinder

out, I had to dismantle most of the car!!!

The picture on page

28 of the book says it all - and the text is even better. Karen quotes

Morris documentation which says the brake master cylinder is "... accessible for replenishment through the aperture revealed when the carpet in front of the driver's seat is lifted."

Her comment to this is "Oh, really! Most people would expect to find this item under the bonnet.".

Her

book is very good because it discusses the influence of the Morris

Minor from a wide variety of positions, and doesn't just talk about the

technical aspects. The colour section has a number of noteable images,

such as the one shown below.

My

comment on this is that you would need more than suction cups to hold a

roof rack onto a Traveller with that amount of luggage!!! But to be

fair, the poster does epitomise what a Morris Minor Traveller is all

about.

David Edwards August 2007

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

Do-it-yourself BRAIN SURGERY & other home skills

by Stewart Cowley, Frederick Muller Limited, 1981, hardcover ISBN 0 584 97073 0

This

book was given to me many years ago by my sister-in-law (thanks Bev!!)

who clearly understands that I am somewhat different.

It is

difficult to describe this book, except to say that it is a delight,

with many ingeniously captioned pictures and much helpful text. There

are twenty different home projects described. For most of them the

basic tools are a hammer and a wheel barrow. Modern OH&S

requirements are anticipated, with general safety issues covered in the

introduction, and specific details (such as making sure that your wheel

barrow is securely chocked while undergoing maintenance) included in

each section.

NASA could have avoided much trouble if their

research had uncovered this book, as the author, Stewart Cowley, in the

chapter on constructing your own orbital hardware, clearly points out

the need to carry spare heat shield tiles and glue to fix them. Given

that this book was first published in 1981, this information, if acted

upon, may have averted the Columbia disaster.

I would thoroughly recommend this book to all prospective engineers, scientists and other practical types.

David Edwards March 2008

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

"The Mummies of Urumchi"

by Elizabeth Wayland Barber, W W Norton and Co., 1999, softcover ISBN 0 330 36897 4

I bought this book as plane fodder at Bahrain Duty Free in the middle

of a long flight, because I thought Kerry might be interested in it. It

was an excellent buy, and I have read it several times since. Kerry

also liked it a lot. One day we would like to travel to Urumchi.

This book tells the story of some bodies, complete with clothes,

discovered in a desert north of the Himalayas, in what is now part of

China. The bodies are caucasian, and it is believed they are of celtic

origin. This is an academic book, with many footnotes and references,

lots of drawings and a number of colour photographs.

If you are interested in textiles and archaeology, then this book is an excellent read.

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

"

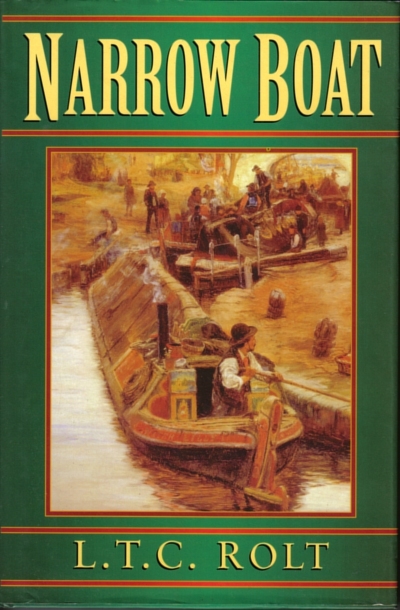

Narrow Boat" by L T C Rolt, Eyre & Spottiswoode, London 1944 ISBN 1 84015 064 5

I have two copies of this book -

the photo above is of a second edition hardcover, published by

Alan Sutton Publishing in 1994. I have another earlier paperback

edition in Hobart.

I have long been interested in industrial archaeology, fostered by a

book my father gave me many years ago of brief biographies of early

English engineers - Smeaton, Brindley, Watt, Naesmith and so on.

Eventually I discovered that LTC Rolt had written a number of

biographies of engineers, and I purchased and enjoyed a number of these.

In 2002 Kerry and I were able to join our friends Debbie and John New

on their wonderful narrowboat for an all too brief weekend in the

Norfolk Broads. It was magical, and I started buying canal maps and

other books on canals. I am not sure now when I first realised that Tom

Rolt had written and published "Narrow Boat" in 1944, this book

ultimately galvanising English enthusiasts into ensuring the survival

of the canal system in a working state.

As soon as I found out, I arranged to buy a copy, and have been hooked

ever since. In 2004 we again joined Debbie and John on their boat, this

time journeying from Marsh to Peterborough. Another very enjoyable

trip at 4 mph!!!

In "Narrow Boat" Tom Rolt describes the year he spent travelling

through the heart of England on a converted narrow boat. He had

modified "Cressy" himself from a Shropshire Union horse drawn fly boat,

by fitting a Model T Ford marinised engine; engineering workshop;

bathroom with bath and chemical closet; stateroom (double

bedroom); sitting cabin with writing desk, "Cozy" open fire type heater

and two easy chairs; fully functional kitchen and a dining room which

doubled as a spare bedroom. All of this in a vessel only 70 ft long,

with a 7 ft beam and minimal headroom. These are the maximum dimensions

which allow passage through the stand narrow canal locks.

The English canal system commenced in the 1761 when the Bridgewater

Canal, engineered by James Brindley for the Duke of Bridgewater was

opened. The subsequent development of the canal system made the

Industrial Revolution possible, as it provided an economical and

efficient means of transport for both raw materials and finished

products. For nearly 100 years the canal system reigned supreme, only

loosing out to railways in the 1850s.

The canal system then went into gentle decline, but was never entirely

closed, because as well as providing a transport system, it also served

as a water supply system. Publication of "Narrow Boat" in 1944 led to

revival of interest in the system, the formation of the Inland

Waterways Association by Tom and others, and the gradual restoration of

the system, which is now used primarily for recreation.

This book is well worth reading, as it provides a unique glimpse into an industrial way of life which is now sadly extinct.

David Edwards April 2008.

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

"

Extreme Ironing"

by Phil Shaw, New Holland Publishers, 2003, hardcover ISBN 1 84330 555 0

I found this book after reading an article on the ABC web site. I

bought two copies from a bookseller in the UK via the internet. The

second copy will go to Beverley, who gave me a copy of "Do-It-Yourself

Brain Surgury and other Home Skills" many years ago.

The most reassuring thing I have learnt from this book is that FoitnBegler didn't lose a member in the water!!!!

David Edwards May 2011

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

"How to Avoid HUGE SHIPS and other implausibly Titled Books"

by Joel Rickett, Aurum Press, 2008, hardcover ISBN 978 1 84513 321 4

This book came from Clouston & Hall in Canberra, and is a complete hoot.

It consists of facsimilies of the covers of the annual winners of the Bookseller magazine's Diagram Prize for Oddest Book Title of the Year, and was published to celebrate 30 years of the Diagram Prize..

What makes it memorable for me is that not only does page 63 feature

one of my favourite books, but page 62 features my favourite page from

this book!!!!

There is companion volume "Baboon Meta-Physics and Other Implausibly Titled Books" which I also have.

David Edwards May 2011

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

The Penguin Dictionary of CURIOUS and INTERESTING NUMBERS"

by David Wells, Penguin Books, 1986, paperback ISBN 0 14 008029 5

This book is an excellent "dipper" - you can just read small parts of it, so it is great for a quick read in bed at night.

As an Engineer, numbers and mathematics are very familiar to me. My

favourite number in this book is 39. This is the first positive integer

that has no interesting properties, so therefore it is the first in the

set of uninteresting numbers!!!

But as David Wells points out, it is also the first number to be simultaneously interesting and uninteresting!!!

David Edwards May 2011

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

The Book of HEROIC FAILURES - The official handbook of the Not Terribly Good Club of Great Britain

by Stephen Pile, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1979, hardcover ISBN 0 7100 0317 X

This is just the book for all those who have difficulty succeeding!!!

Following the usual format, there are a number of chapters in this

book, covering such topics as The World of Work, Law and Order,

Culture, the Stage etc. etc.

Page 19 provides details of The Worst Canal, which was constructed

through porous limestone and which required water to run uphill. While

it is true that the canal was constructed in Ireland, the designer was

an Englishman.

Page 39 annoints The Least Successful Car - the Ford Edsel.

I have a copy of the first edition, which includes an application form

for the Not Terribly Good Club of Great Britain. As one would expect,

this was a complete failure - so many people applied to join the club

that membership rose and the club became a roaring success. Under the

terms of its constitution it had to close immediately!!!

David Edwards May 2011

Links to: Introduction or Contents or David & Kerry Edwards Home Page

Web page designed by

David Edwards

Last

updated 27 May 2011

Copyright

© David Edwards 2007, 2008, 2011